- Home

- Diana Altman

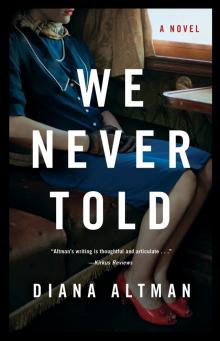

We Never Told Page 9

We Never Told Read online

Page 9

Many of the people who walked passed us were tough-looking boys accompanied by sad-looking women and men with briefcases. Probably the mothers and the lawyers. The judge, so it seemed, clumped me in with juvenile delinquents. “What do you suppose he did?” I whispered to Joan when one of them walked by. “Stole something,” she said. “I wonder what he wanted so much.” There we sat for years and years and at last the door opened and out came our parents and their lawyers. My mother’s face was contorted in anger but even in her fury she had a hesitant alone quality that was heartbreaking and attractive. She noticed Joan and me sitting on the bench and her angry face turned worried. Her worried glance infuriated me because I believed she should have been able to predict that her actions would land us in Children’s Court. The staccato of her high heels grew fainter as she walked away down the corridor, small next to beefy Saul Ruben.

Clement Monroe, his shoulders even more rounded, his face even more worried, raised a regretful palm in farewell to Joan and me, was kind enough not to smile, and walked away down the corridor. My father, aglow with victory, said, “Turns out the judge was a graduate of New Rochelle High, thinks it’s top notch.”

CHAPTER SIX

Every Wednesday evening, per court mandate, Seymour had the right to be with his daughters. He drove to Scarsdale in his Pontiac and parked in front of the entrance to our building. He never asked to see our apartment. I assumed it was because he wanted to avoid his ex, yet I thought it odd that he didn’t want to check out where his daughters were now living. To not even know the look of your own daughter’s bedroom seemed too distant. Had we said to Mother, “Daddy wants to see the apartment,” she would have agreed, perhaps gone into her bedroom and closed the door until he was gone.

Each Wednesday evening, the intercom buzzed. Joan and I took the elevator down eight floors and found Seymour standing in the lobby dressed in his cashmere overcoat, his fedora at a rakish angle. His expression was mortification whitewashed with cheerfulness. He had just been required to announce himself to the doorman as if he was the plumber or a deliveryman. Seymour had to stand before Kyle stripped of all authority, waiting for his own daughters to come from a home where he was not welcome.

The Colonial Inn was a restaurant in an antique house about a half hour from our apartment. The wallpaper was a design of shepherds with their flocks, the ceiling was wooden beams, and the floor was wide floorboards from some gigantic tree that perhaps shaded the pilgrims. The Colonial Inn was pure New England though in a suburb of New York City. The patrons were mostly gray-haired people who sat across from each other eating in a cud chewing, thoughtful way. The hostess was familiar with Seymour, and that made me sad because it meant he ate there even when it wasn’t Wednesday. I didn’t like thinking of him sitting at one of those wooden tables all by himself. The first time the hostess met us she said, “Mr. Adler! What gorgeous granddaughters you have!” They had their little routine. He looked at her and said, “What? What’s this?” and took a coin out of her elbow and she said, “Oh, you!” and bopped him on the arm with the menus.

Every Wednesday, we ordered the same things. I always had roast turkey with extra cranberry sauce, Joan had fried chicken with mashed potatoes smothered in gravy, and Seymour had New England boiled beef dinner with boiled potatoes and boiled cabbage. For dessert, Indian pudding. We never had what could be called a conversation. Seymour never asked about our friends, our studies, our hopes, our concerns. Just as he didn’t want to know anything private about us, so did he not want us to know anything private about him. To prevent intimacy, he drowned us in an avalanche of words. “It’s a dandy story,” he said referring to a script he was reading. “The butler enters and says, ‘If you don’t mind, Sir,’” Seymour used a haughty British accent. “‘I do mind, Jenkins,’ says the Earl,” and Seymour used another voice. “‘How many times must I say do not bother me while I’m working on my stamp collection?’” Joan and I kept our eyes lowered. “Enter the wife. ‘Murdock, you are not dressed. The party starts in an hour and here you are in your riding clothes.’” Seymour made his voice high to sound female. “The basic plot is that the wife’s sister has stolen some jewels from their aunt, but not because she’s a bad person. It’s because her son is ill and she needs the money. When she enters she says, ‘tisn’t fair Madeline. Tisn’t fair atall.’” I found Seymour’s female voice insulting as if all there was to sounding female was pitching the voice into a shrill register. He described the scene of the two sisters sitting in the drawing room drinking sherry, and the clock ticking on the mantel, and the close up of the husband when he comes in and realizes that the sister is not the real sister but an imposter, and he wonders why his wife doesn’t realize she’s talking to an imposter. Then he looks at his wife and realizes it’s not really his wife but also an imposter, and that the two women in his drawing room are total strangers. So he backs out and tiptoes down the hall to find the butler. “And he says, ‘I say old chap, have you noticed anything peculiar?’”

How could Seymour go on and on like this? Why did this happen every time he took us out to dinner? His torrent of words stopped only long enough to pay the check.

Driving back to Scarsdale, I turned on the radio because I thought that might shut him up. I couldn’t bear to hear one more meaningless word out of him. That hurt his feelings. Every Wednesday, it was the same unsatisfying encounter. Nothing was moved forward, nothing was settled, we became no closer. Every week as he turned into the entrance of our building he said, as if it was an afterthought, “Mother doing all right?”

“She’s okay.”

“Seeing anybody?”

He wanted us to spy on her? Did he imagine getting back together? His interest in her was not reciprocated. She never once asked about him. “I don’t know,” one or the other of us lied.

She was seeing someone. She met Phil Goodman at her Great Books course at the New School in Manhattan. Mother regretted not going to college, blamed her mother for insisting that she become a dancer. Now she was determined to make up for lost time. I found her reading excerpts from the Illiad and Alexander Pope and Socrates. She said that sometimes the teacher praised the questions she asked. She said that she planned to take the SATs and go to college. To be helpful, I suggested she get an SAT tutor and was surprised that my suggestion hurt her feelings. “But there’s math,” I said. “There’s math questions.” She turned from me. “Mommy, you can’t learn math by yourself.” Maybe she didn’t know that hiring a tutor was common, that even the smartest kid in class sometimes needed a tutor to prepare for the SATs. In an injured voice she said, “I can take care of myself thank you.”

Phil Goodman was an informal person, sprawled on the sofa in a relaxed way that I didn’t understand. I was used to three-piece suits, starched shirts, cuff links, and polished shoes. His shirts were open at the neck, his shoes were scuffed loafers, and his socks weren’t high enough so when he crossed his legs I saw his hairy calves. It was comforting to see my mother with a man her own age. Made her seem younger, more vivid. He was a teddy bear sort of person with brown hair and warm eyes. His masculinity was of the cuddly sort. He was a psychologist who worked at a VA hospital. He was studying the two hemispheres of the brain. One of his patients was a person who bumped into the edges of doors because he had no perception of the right side of his body. His patient didn’t know what one whole side of his body was doing. Synapses that were supposed to be shooting back and forth were not. I liked Phil Goodman but wondered why Mother chose him. Her father had outfitted her so she could attract a wealthy man, yet even I knew a psychologist working at the VA did not earn a lot of money.

Mother, as it turned out, enjoyed cooking and was good at it. Often I found her in the kitchen experimenting with soufflés, omelets, and different kinds of dough. Sometimes I thought she would have been better off in her marriage with less money. Without a maid, she would have had to devote herself to the domestic skills that she enjoyed and was good at. I wondered how l

ife in New Rochelle would have been with Mother stirring at the stove and the rest of us at the kitchen table saying, “Yum!”

When Phil Goodman came to dinner in Scarsdale, Joan felt no obligation to charm him. Sitting across from me at the new dining table, eating from the plate that used to live in New Rochelle and using the silverware that used to live there, she chewed and kept her eyes down. Phil told us about the research he was doing for the benefit of people with epilepsy. The idea was that if the two hemispheres of the brain could be separated, then maybe the flash that leapt from one side to the other triggering the seizure would be blocked. He was about to actually try this, had a patient who was about to have the two sides of his brain separated. “But what if it doesn’t work?” I said. Joan finished her dinner, carried the empty plate to the kitchen, stuck it in the dishwasher, then went toward her bedroom. “Don’t you want dessert?” Mother asked. Joan said, “No. I’m done,” and closed the door to her bedroom.

Joan didn’t seem to care that Mother was happy getting dressed to go to a movie with Phil or out for a day at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What our mother did was of no concern to Joan unless it got in her way. It was as if we were three roommates living in an apartment together. One evening, as I was absently looking at the calendar on the wall, I realized that none of the squares were filled in with the word Phil. Then I realized she hadn’t gone out in a while and he hadn’t come over. “Did you break up with Phil?”

“What?”

“Did you and Phil break up?”

“He wasn’t for me.”

“What happened?”

“Nothing happened.”

“So why’d you break up?” I wanted her to hurry up and get married. Her family in Chicago was tapping its fingers. I overheard defensive conversations on the phone. “Mama, I’m not going to marry just any old person just to be married.” My mother was in a degraded position and I wanted it to stop.

“Phil wasn’t for me. He had no background, no culture, no breeding. A man who has never been married by the age of forty-seven is set in his ways.”

“What were his ways?” I wanted to know.

“I don’t know, Sonya. What difference does it make?”

A few months later the name Jerry was in one of the calendar squares. A lawyer with an apartment in Manhattan and a summer home in Amagansett, she met him in a Modern Poetry class at the 92nd Street Y. He was a well-nourished man whose wife died of cancer. When he came for dinner or when he arrived to take my mother out for a date, he did not try to draw me out in conversation. He had children of his own and knew there was no reason to make me like him until he was sure he liked my mother. When the weather got warmer, we visited Jerry Applebaum at his summer home, a graceful place by the ocean. Then one day his name was gone from the calendar squares, and Mother told us that he was engaged to the nurse who had looked after his wife. “A mama’s boy,” Mother said by way of explanation.

Max Greenstone meant to bail his daughter out of a difficult situation, not support her for the rest of her life. “What job, Mama?” I heard her say on the phone. “What exactly would you have me do? Be a secretary? Yes, of course I know how to type. Do you have any idea how much a secretary makes? Be realistic, Mama. I can’t live on a secretary’s salary. Oh, all right. I’ll go be a waitress. Would that satisfy you? I’ll go get my bottom pinched and take tips.” These phone calls, like music sung off key, were painful to hear. Grandma was relentless, called two or three times a week. I hoped some new man would appear to save Mother but week after week there was no one.

CHAPTER SEVEN

At first, the requirement that Joan and I sleep at Seymour’s house every other weekend was not onerous because we wanted to be in our familiar bedrooms and we wanted to be with him, the other person suffering from the divorce. The three of us were struggling for equilibrium and rooting for each other though this was never expressed in words. However, the symbolic him was quite different from the actual him. Being with the actual him was a chore. Joan and I much preferred to be with our friends. He was always grouchy and seemed to expect us to take care of the house, to vacuum and scrub the toilets. I would have liked to have been a fairy tale good girl but I wasn’t. My boyfriend Pete lived a few blocks away, so we took the bus to the movies Saturday night and on Sunday afternoon we did our homework together in between kissing in his bedroom still decorated with cowboys from when he was little. Often on weekends in New Rochelle, Joan and I were with Seymour less than two hours.

I wished my father would not make pancakes for us because he didn’t cook them long enough so they were like mucous inside, and it was embarrassing seeing him in an apron at the stove. The kitchen was a mess and Joan and I felt put upon cleaning up after him, though we understood he meant the pancakes as a loving gesture. It was as if he was trying to show us how the weekends should be, a loving little family eating pancakes for breakfast. The visits turned into guilt fests. He complained that I didn’t change all the beds. He cast me in the role of housekeeper, and I suspected it was because I was a girl. Girls were supposed to do that sort of thing. On the other hand, I believed a more loving daughter would help her father around the house. Someone good, like Cinderella, would have the patience to scrub the burn off the pancake griddle. My father seemed to blame me for not being able to make his life better. He screamed at me to get off the phone, to play my music more softly, to stop sleeping so late in the morning.

One warm spring day, my boyfriend Pete came to pick me up in jeans and a T-shirt and my father screamed at him, said he should show some respect for a young lady and dress more appropriately. Pete and I both understood that Seymour was old school but that didn’t make the tirade any less offensive. Pete did not deserve to be treated scornfully. He won the national science fair in ninth grade, and MIT had already told him that he would be accepted if he applied. He had invented a computer that could recognize his voice. Had my father taken the time to talk to Pete, he would have discovered an interesting boy.

Because Joan and I were often unavailable to Seymour on our every other weekend visits, we were scrupulous about being available every Wednesday night for dinner. One Wednesday, much to our surprise, we saw that someone else was in his car. The head almost touched the ceiling and the person’s width overwhelmed the front seat. Who would dare intrude on visitation night? When Joan opened the back door, the car light went on and, as we climbed into the back seat, a very beautiful very fat woman turned from the front seat to greet us. Her nose was finely chiseled with slightly flaring nostrils. Her full lips were painted the color of merlot, large brown eyes, arched eyebrows, and delicate shell-like ears. She wore a silver turban and dangling earrings. She waited for each of us to say our names then turned back to spare twisting her neck around. Everything about her, including her attractive perfume that changed the atmosphere in the car, announced that she had as much right to be there as we did, which I took to mean she was my father’s lover. He said, as we drove away from the apartment building, “Miss Morrison is an opera singer.” She corrected him, “Annabelle.” She wasn’t going to do any pretending in front of girls old enough to understand. She had a womanly voice in the alto range. She had come to his office, he explained, because he was casting an opera singer for a new MGM film. “Miss Morrison,” he insisted upon that formality, “has performed at all of the finest opera houses. At the moment, she is expecting Maestro Bocabella to contact her with plans for her next world tour.” We said nothing. “Miss Morrison,” he continued, “mentioned that she wants to lose weight. I said to her that nothing is more effective than working outdoors in the garden.”

“Let’s hear you sing,” I said.

She turned to see which of the girls had challenged her. Our eyes met. She was not cowed by cheeky girls. The contralto boom that came out of her vibrated the windows and almost blasted us to Mars. “Holy moly!” I cried. She laughed, a big laugh that filled the car. When we got out of the car at the restaurant, I saw she was massive as a b

reakfront, about a foot taller than my father and was wearing a red velvet cape.

The next time we slept at his house, she was there and after a few weekend visits we realized she had moved in. Her bedroom was in the attic, but when we snuck up there to inspect we saw it wasn’t a real bedroom. It was more like a child’s clubhouse, mattress on the floor, her things scattered all around. The attic bedroom was for show. Obviously, she slept downstairs in Seymour’s bed except every other weekend when Joan and I were there. He began to refer to her as his housekeeper. I was sorry he didn’t understand that I was happy he found a companion.

Like a dog marking its territory, Annabelle marked the furniture in the house with what amounted to her logo, a pink rose with a dew drop on one petal. She was good at painting that one particular rose. The fireplace screen got a rose. The backs of wooden chairs got a rose. One weekend, I discovered a pink rose painted on the headboard of my bed. Couldn’t she tell it was an antique? How could my father let her? That bed was mine. Or was it? Most of the time, that bedroom was empty. She believed she was improving the furniture. When the toilet seat lids got a rose, I began to wonder if Annabelle had enough to do.

Her primary work was creating the wardrobe she would need for her upcoming world tour. Maestro Bocabella was biding his time waiting for the best moment to put her back on top. The sun porch, a large room with walls of windows and views of the lilac trees in the backyard, became her atelier. Gone was the ping pong table and the remains of any toys that Joan and I once used. Now the sun porch was dominated by a large sewing table heaped with cases of bobbins and thread, boxes of sequins, tape measures, dress patterns. Bolts of fabric were stacked against the walls, brocade, taffeta, suede. Dress forms, they looked thinner than the real woman, wore Annabelle’s latest creations, mostly capes made from vicuna or velvet, some trimmed with chinchilla. “This,” she said as she showed me a new bolt of gold Lamé, “feel the texture, this will be a dinner garment when I’m on tour in Roma. The Italian women are more chic than the French. The Italians have that je ne sai quoi … ” She thought for a moment then said, “Sprezzatura!”

We Never Told

We Never Told