- Home

- Diana Altman

We Never Told Page 2

We Never Told Read online

Page 2

From our compartment window, we could see the hustle and bustle on the station platform, people rushing here and there, men with briefcases, women holding the hands of children, a man slumped in a wheelchair being pushed by a nurse. Mother erupted with one of her alarming sighs. It was the very sound of her, three fast inhales that sounded like sobs then an exhale that sounded like a moan. “What’s the matter?” I asked.

“What?”

“What’s the matter? How come you sighed like that?”

“Like what?”

“Like how you just sighed. Are you sad?” I hoped my question would show my mother that I loved her and cared about her happiness.

“Sad? Don’t be silly.”

But I wasn’t being silly. In private, I imitated my mother’s sigh so I could understand if it was a normal adult woman sound. No matter how I mimicked it, it always came out sounding like something from deep within, a sigh that spoke of despair.

“Hey! It’s starting!” Joan announced. We watched the station platform recede as the train hurtled through a tunnel. The window turned black, became an unflattering mirror. Then our ghoulish faces evaporated and we could see into the windows of apartment buildings close to the track, old brick buildings with fire escapes like vines. Some of the people were just sitting at the window looking blankly out, smoking a cigarettes. There were long stretches of not seeing much but empty station platforms lit up as if for no reason because the train just sped by, and there were towns with rows of street lamps and lights at the windows of the few houses and always the sound of the wheels on the tracks, chuck-a-chuck, chuck-a-chuck, chuck-a-chuck and the pleasant feel of forward motion.

Joan dealt out Crazy Eights with intense concentration, placing the cards before our mother and me in neat little stacks. Then we played the drawing game. Mother made a scribble on Joan’s sketchpad and another on mine and we had to make a picture out of it. We had high standards. If our mother drew a circle we did not turn it into a face. That would be too easy. We didn’t turn rectangles into houses, either. Glad to be occupied, we took our time. When we finished, Mother burst out smiling and said, “That is so clever! I can’t believe you made that out of what I drew!” Without Seymour, Mother was a good companion, easy to talk to, easy to make laugh. She told us our favorite story: When she was a child in Texas, climbing the water tower was forbidden, but a boy did it anyway and fell in and couldn’t get out. She ran to the nearest farm and the farmer hitched up his wagon and galloped his team to the water tower, fished the boy out, and put him in the wagon. The water bounced out of the boy as the horses trotted along. “So he didn’t die?”

“No. The water bounced right out of him.”

“How did you know it got out of him?”

“Because he sat up.” It was as if Mother was on a dimmer switch and was only fully bright when her husband wasn’t there.

The dining car was a fairyland, white table cloths, silverware, martini glasses, flowers in vases, men in suits and ties, women dressed up, all hushed and sparkly. A small pewter bowl of water was set before each person. Years before, Joan lifted hers and drank it. Now we knew to dip our fingers in the water and wipe them in a dainty way on our napkins. My mother, in her beige cashmere sweater with a paisley scarf tied cowgirl style around her neck, sipped Harvey’s Bristol Cream and wrote our menu choices on a card with the pencil left on the table for that purpose. She wrote roast lamb with mint jelly for herself, hot turkey sandwich for me, and egg salad sandwich for Joan. We buttered rolls and ate them, then asked for more and ate those too. We ate our dinner with the pleasant clinking of ice cubes in cocktail glasses at the other tables, soft conversation, and the perpetual sound of wheels on track. Time was suspended, we were being carried along. For dessert, chocolate cake and vanilla ice cream. Then chocolate covered after dinner mints on a pewter plate. We ate every mint. Mine was the only mother I knew who was not bothersome about sweets. Our kitchen cabinets at home were stocked with Mallomars and Oreos. She expected me and my friends to help ourselves when we came home from school. She liked candy too, and hot fudge sundaes, and pies and cakes. It was our good luck that Ruby at home was an excellent baker.

When we returned to our compartment, it was no longer a sitting room but a bedroom, the seats now converted into bunk beds. The porter made the bed so crisply I had to wedge myself in. As I lay there sandwiched tight between top and bottom sheet, I worried. Would the sound of the wheels on the track keep me up? Did my aunts and uncles know Mother intended to divorce? Did my cousins know? What could be more embarrassing? I was in a mess, and they’d all know it. Would they look at me with pity?

We were saved from the chaos of LaSalle Street station by Grandpa Greenstone’s chauffeur, whose bearing was so regal I didn’t dare hug him though I wanted to. Jordan led us through the crowds and out to the street where a black Cadillac limousine waited at the curb. When the Red Cap finished heaving the suitcases into the trunk, Jordan tipped him and I wondered if one black person tipping another black person was different from a white person tipping a black person. Did the Red Cap resent Jordan? Did Jordan look down on the Red Cap?

Sunk in soft gray upholstery, we felt the car glide smoothly out into traffic. People on the sidewalk stopped to watch the car swim by with its tinted windows and chauffeur at the wheel in black cap and uniform. I thought of rolling down the window and waving to the people on the sidewalk with my hand backward like the Queen. My sister, on the other hand, was not impressed by money. She didn’t seem to appreciate that Grandpa, who only went as far as eighth grade, was once poor and because of his struggles and perseverance could now buy himself a Cadillac limousine. Joan might as well have climbed into a taxi. She collapsed the jump seats, set them up, collapsed them, set them up. Mother snapped, “Stop playing with those things for heaven’s sakes!”

We drove through the streets of South Chicago where black men were idle on the stoops of brick buildings. Dressed in winter jackets, they followed the car with sullen faces. Did they envy Grandpa Greenstone’s chauffeur? Did they hate him for driving white people? Did he care about their opinion?

When my mother withdrew her warmth from us, I could see it in her eyes. Her gaze turned shallow. She looked at Joan and me as if we were objects in a shop and she had to decide if we were worth the price. That we were not worth the price was evident in the impatient way she brushed aside Joan’s bangs. “Get your hair off your face,” she said. I knew from previous visits that her tension would mount the closer we got to her mother. Her mother was the harsh judge who lived inside her head. My mother was about to present her daughters, and we were not perfect. She spit on her hanky and wiped a mote off my cheek. “Yuck!” I rubbed the spot again and again trying to get the saliva smell off.

In the elevator, the other people had to get off on floors with numbers. Only we were allowed to go all the way up to PH. The elevator man, wearing white gloves, pulled back the brass gate and Mother, Joan, and I stepped out into a private vestibule. My grandparents’ apartment was like a house perched on top of a building. Mother rang the doorbell and chimes made a melody inside. A mechanical bulldog stood guarding the door, a toy that Grandpa lugged home from China. It made raspy squawks when I pulled its leash. I saw the toy as Grandpa’s twin, a stocky fellow with jowls and a turned down mouth. I pulled the leash again and again. Joan said, “Let me do that,” and she pulled the leash and while metallic snarls ruined the quiet of the exclusive foyer, Mother said, “She always does this. Keeps us waiting. Makes us stand here.”

When we heard footsteps behind the closed door, Mother said, “Finally,” as if we had been standing there for hours. The door opened. A tiny woman, barely five feet tall, was so shy the force of our presence impelled her backwards. Instead of drawing toward us for an embrace, Grandma Greenstone was so overwhelmed she went backwards and might have continued on forever except that she was stopped by the first step of a grand staircase. She stood there helplessly and batted at her gray pompadour with th

e back of her hand. She was perfectly groomed in a tailored dress and low-heeled pumps. I was continually impressed by how tiny and insignificant Grandma Greenstone was to me and how gigantic she was to her daughter Violet. “Hello, Mama,” my mother said in a dead voice.

I went forward and gave Grandma Greenstone a hug. As always she said, “Is that all I get?” As I squeezed her harder, I wondered why she would expect more? This final hug was phony; the first one was appropriate to what I felt for her. “Ah,” she said, “that’s better.” Then Grandma Greenstone turned a critical eye on me, took my chin between her thumb and forefinger and gave it three firm tugs. Grandma believed a child’s face could be molded. She wanted us to have strong chins. It was important for a girl to be beautiful and there was a danger that Grandma’s offspring might inherit her receding chin. It was part of her duty to uplift her family in every way possible. I appreciated Grandma’s effort to make our lives easier than hers had been. I could appreciate this effort because I saw its contrast in my father’s family. The old ways were the best ways with the Adlers in New England. Here in Chicago, in everything Grandma Greenstone did, I saw the struggle to leave behind the girl she used to be, a poor girl living in a shack on the plains of New Mexico with five sisters and immigrant parents who barely spoke English. Grandma’s penthouse overlooking Lake Michigan was the dusty green of sagebrush, the tan of tumbleweed, and the brown of mesquite. The carpet was sagebrush and so were the walls. I moved aside so Joan could have her turn. She gave Grandma a hug. “Is that all I get? Ah. That’s better.” Then three firm tugs to Joan’s chin. To her daughter, Grandma said, “Violet, where is your hat?”

“I didn’t wear a hat, Mama.”

“No hat? Why not? You must wear a hat. The weather is cold.”

“Okay, Mama. I’ll wear a hat.”

“Do you have a hat?”

“Oh, for heavens sakes, Mama.”

“Your hat should be on your head, Violet, but I do not see it on your head.”

“Okay, Mama. Enough.”

“If you do not have a hat with you, then we must get you one.”

“Fine, Mama. Fine. We’ll get me a hat.”

As Grandma took our coats and hung them in the downstairs closet, she refused help even though she was obviously struggling with the weight of the coats, I hurried to the den where Grandpa Greenstone was beached on his Barcalounger, watching the only color television I had ever seen. Color television, everyone knew, was experimental and expensive. Shoes off, feet raised, belt buckle undone to allow for maximum pooch, Grandpa Greenstone took his cigar stump out of his mouth, waited for my sincere kiss on his jowl, and rewarded me with the music of his chortle. “Hello, honey,” he said and we looked into each other’s eyes long enough to say what we meant, we loved each other. He was such a character with his snakeskin belt, pointed-toe pumps, socks with swirls on the cuff, and a silk shirt custom made in Hong Kong with his initials over one plump breast. His watch was a solid gold Patek Phillippe. On one plump pinky was a star sapphire ring. Did he know his daughter intended to get divorced? Was he secretly seeing me as a helpless little victim?

Joan entered the den. “Hello, honey,” Grandpa said, “Commere and give your ole grandpa a smooch.” Joan thought Grandpa Greenstone was a bully. She came to the side of his chair, planted a dutiful kiss on his cheek then retreated immediately behind the heavy sage green drapery that Grandma kept closed over the windows so the sun wouldn’t fade the sage green slipcovers and the sage green carpet. I joined Joan hiding back there behind the drapery. Hidden by yards of heavy fabric, we looked out at the rooftops of Chicago and the expanse of Lake Michigan stretching to the horizon like an ocean. Lake Michigan was unreliable. It got all churned up and sent waves crashing over Lake Shore Drive. Like an ocean, the far shore was invisible but if you sailed across you wouldn’t come to Sumatra but Indiana or Wisconsin. I thought the lake should be more humble with such a pedestrian shoreline. We stood gazing out at tiny cars below and seagulls flying not above but beneath us. We heard our mother come in. We couldn’t see her through the thick fabric. “Hello, Daddy.”

“Hello, honey,” he said and chortled.

“What’s this you’re watching?”

“Wahl now, less see. That fella he’s the detective. Seems some woman turned up dead. Set and watch with me.”

“Mama wants us to unpack so we can give our dresses to Willa.”

With a lowered voice he said, “How’s everything, honey?”

“He says no. It’s a flat no. He will not. Period.” Were they talking about the divorce? “Hey you two, come upstairs and unpack.” We thought we were invisible behind the curtains. “Did you hear me? I said come upstairs and unpack.”

“We will,” Joan called.

Mother whispered, “This could get expensive, Daddy. He’ll drag it on for months.”

We couldn’t go upstairs and unpack before greeting Willa in the kitchen or before sniffing in the living room like puppies getting reacquainted. Across the hall was Grandma’s version of the front parlor, a showroom for guests. Not trusting her own taste, Grandma hired a decorator to fashion a sophisticated living room. Here was Versailles, brocade upholstery on stiff sofas and chairs that demanded straight posture. Grandpa Greenstone played cards with other men at the Standard Club in downtown Chicago, but Grandma had no friends. The room just sat there with its hair combed.

In the kitchen was Willa, skinny and cringing as a coyote. Her maid’s uniform hung on her skeleton like skin molting. Embarrassed by her buck teeth, she hid them with her palm when forced to smile. This she did when we burst into the kitchen and ran to her calling, “Hi Willa! It’s us!” She made a singsong sound, um hmm, um hmm, a special kind of hum that never came out of white women. Grandma’s relationship with Willa was more intimate than Mother’s was with our maid. I didn’t know much about Ruby, but I knew that Willa had six children and that Grandma Greenstone made sure they had warm winter coats and kept the appointments Grandma made with the pediatrician. When Willa went home at night to somewhere in Chicago, she carried bottles of vitamins, boxes of detergent, and food. She depended on Grandma to make the necessary appointments with the telephone company and the plumber. Willa, so whispers said, got involved with the wrong man and Grandma paid for Willa’s abortion. Before we had Ruby, we had a series of maids, each one lasting one or two years, all of them quitting in an acrimonious way. Willa and Grandma had been together for more than twenty years. I had no idea what to say so I said, “How are you?”

Willa whispered, “I be fine.” She never said our names, probably because she couldn’t tell us apart. The kitchen was large with several pantries and sinks. Eggplant slices were sweating in colanders, potatoes were waiting to be peeled, and Willa’s famous Monkey Bread was rising in its pan. “Willa, what’s for dessert?” This was a set up. We wanted to hear her say it wrong. “Sherby ice cream.”

The guestroom, also carpeted in sagebrush with sagebrush walls, was at the end of the sagebrush upstairs hall. I was aware in Grandma’s apartment of the influence of interior design because it felt so different being here than it did being in my home. My house was obviously home to someone who thought about color, arrangement, and texture and spent a lot of time in stores looking for the perfect item. There was something pleasing to look at everywhere in our house. My mother loved decorating rooms, and it made me sad that she expressed this passion and talent in a negative way. She said, “You’re a slave to a house.” In Grandma’s home, there was almost no color and almost nothing beautiful to look at. It worked upon my body in a different way from the rooms in my house in New Rochelle. It felt less demanding, like a note that was muted.

My mother was standing at the window in the guest room. She often stared off into space, went someplace else, was not even really in the room anymore. It was frightening and peculiar. To bring her back to me, I said something silly. “Why can’t she come up and get them?” Mother didn’t seem to notice that I’d come into the gue

st room with its twin beds and a cot set up for either Joan or me, whichever one lost the coin toss. “Why can’t she come up and get them?” No answer. “Mommy, why can’t she come up and get them?”

“Who?”

“Willa.”

“What?”

“Why can’t Willa come up and get the dresses.”

She turned from the window and I could see her adjusting, gathering strands together as she focused on me and came down from wherever she went in those moments of absence. “What?”

The bureaus, tumbleweed tan, had been emptied for our use, but we couldn’t hang our dresses in the guestroom closet because it was kept locked. It contained Grandma’s private treasures and no one was allowed in. Aunt Dovey Lee, my mother’s younger sister, called the closet Fort Knox. It held riches brought home from Europe, Japan, and India. Only upon Grandma Greenstone’s death would we know what was in the closet. I wondered how long we would have to wait to know what was in there.

Wrinkled dresses in hand, Joan and I found Willa in the dining room taking gold-rimmed plates out of velvet envelopes and wiping each one with a dishcloth. We, the family, were the only ones who ever saw the china, crystal, and silver brought home from Europe. Grandma and Grandpa never had dinner parties for friends. My own parents had many dinner parties but the friends were all my father’s. He liked filling up our living room with the hum of conversation and ice clinking in cocktail glasses and bursts of laugher. Grandpa, on the other hand, liked being by himself in his home. When they were alone, my grandparents ate in the kitchen at a Formica table and watched the six o’clock news on a small television. The dining room, this evening, would come out of its coma. “Here’s our dresses,” I said hoping Willa understood that it wasn’t my idea that she should stop whatever she was doing to iron my dress.

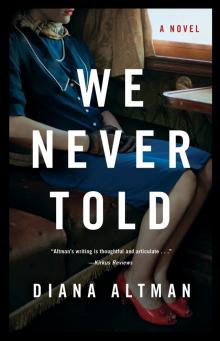

We Never Told

We Never Told